The early 1990s brought us two high-concept comedies that boldly challenged our traditional notions of the meaning of life. The first would be the classic Groundhog Day (1993), a peak Bill Murray film in which a man relives the same miserable day again and again for what could be centuries for all we know (though the filmmakers later claimed it was merely a decade). Smuggled in between Murray’s snarky comments is a surprising message of hope and resilience that becomes downright moving when you think about it. When faced with an endless expanse of meaningless repetition, our jaded hero at first indulges in carnal pleasures, then descends into a suicidal despair when it all grows boring. Eventually, he learns to wrestle meaning from his endless winter, not through some profound mystical epiphany, but through the everyday experiences of love, kindness, delight, learning, and the never-ending challenge of becoming a better person.

A similar film that demands multiple viewings is the brilliant Defending Your Life (1991), a satire written by, directed by, and starring Albert Brooks. Brooks plays Daniel Miller, a neurotic, materialistic, recently divorced ad man who, in a moment of truly dark humor, drives his brand-new BMW into an oncoming bus. He wakes up in Judgment City, a way station in the afterlife where the newly dead must prove that they are worthy to move on to a higher plane of existence—not heaven exactly, but a place where they will continue to grow and explore, free from the limitations of life on Earth.

The universe, however, has a vicious joke in store. Rather than providing the dead with clouds and harps, Judgment City simulates an international conference from hell, with its sanitized hotels, annoyingly chipper staff, mind-numbing lobbies, and bland concrete plazas. (Believe it or not, some of the exterior shots were adapted from the visual effects used in Total Recall, from the matte paintings to the tiny projector inside a train.) While the weather is always perfect, and the visitors can eat all the junk food they want, the relentlessly “normal” setting makes a few of the newly dead wonder if they are being punished. Even worse, the humiliating judgment process forces the defendants to sit through outtakes of their lives, while lawyers bicker over the cosmic significance of every major life decision. Daniel, a perpetual sad sack, awkwardly relives the time he crumbled while giving a speech, or the time he chickened out of making a small investment that would have made him rich. There’s even a blooper reel that makes the judges giggle.

According to the rules of this universe, the main purpose of life on Earth is to conquer one’s fears. Daniel’s lawyer Bob Diamond (Rip Torn) puts it this way: “Fear is like a giant fog. It sits on your brain and blocks everything…You lift it, and buddy, you’re in the for the ride of your life!” Of course, this pep talk only makes Daniel more scared. “I’m on trial for being afraid!” he whines. Bob tries to reassure him with some corporate doublespeak. “Well, first of all, I don’t like to call it a trial,” he says. “And second of all, yes.”

To complicate things, Daniel falls in love with Julia (Meryl Streep), a recently deceased woman whose own trial is going much differently. A warm, outgoing mother of two, Julia has conquered her fears so convincingly that even her prosecutor admits to watching her outtakes merely for enjoyment’s sake. Her success in life both attracts Daniel and makes him realize his own inadequacies. While he may have dated women who were out of his league in the past, here his love interest is destined for adventure in another realm of existence, while he resigns himself to being demoted back to Earth for nearly the twentieth time. “I must be the dunce of the universe,” he says.

This business about conquering fear and expanding your mind as the main purpose of life might sound a bit New Age-y for some. Certainly it is a concept that doesn’t get the nuance it deserves in a ninety-minute screenplay. But the film uses this idea to create a surprising payoff, a truly raw moment in which Daniel realizes how badly he has failed himself, and how narrow his view of life has become. These days, a flawed, unlikable protagonist is often used as a joke, accomplishing little more than mere shock value. But Daniel is all of us, a scared little human hypnotized by trivial matters, convinced that he still has time to talk his way out of his failings.

Even better, the film gives Daniel a chance to redeem himself, not through some contrived therapy-induced revelation, but through his love for Julia. Yes, her character veers a bit into Manic Pixie Dream Girl territory (though in Streep’s able hands, it’s difficult to notice), but in this case, the film makes it clear that she is the superior of the two characters, the leader, and not merely a stepping-stone for the protagonist.

In creating this intriguing world, Brooks avoids the problems that many movies face when dealing with a traditional understanding of the afterlife. Namely, how do you create tension in a place that is meant to be the sum total of all our desires? What story is left to tell when a person suddenly learns all there is to know, suffers no pain or hardship, and never needs to improve or strive for anything ever again? When such a blissful afterlife is actually confirmed within the confines of a story, it often undercuts the plot and the characters’ motivations—take Ghost (1990), for example. Recently deceased Sam (Patrick Swayze) tries to warn his girlfriend Molly (Demi Moore) that people are trying to kill her. But why bother? He now knows—beyond any doubt, mind you—that she’ll simply go straight to paradise if she dies. Or look at Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners (1996), in which mischievous ghosts flee from a Grim Reaper-like demon. But at the end, we discover that the Reaper’s touch merely frees the spirits from their limbo and sends them to heaven. So what was the point?

It is no wonder that movie critic Roger Ebert was a fan of Brooks’ film. Ebert produced some of his most moving prose in the months leading to his death in 2013 from cancer, and many of the ideas in Defending Your Life are echoed there. Starting with his television program, Ebert defended the film when partner Gene Siskel argued that the script lost its way by moving from a biting satire to a love story. In contrast, Ebert felt that the sweet, optimistic ending was well earned, sending a refreshingly hopeful message to the audience. Later, in his 2011 memoir Life Itself, Ebert talks about his deteriorating condition in a way that would impress the administrators of Judgment City. Rather than fearing the end and the unknown that lies beyond it, the author stubbornly writes, “I have plans.”

I don’t expect to die anytime soon. But it could happen this moment, while I am writing. I was talking the other day with Jim Toback, a friend of 35 years, and the conversation turned to our deaths, as it always does. “Ask someone how they feel about death,” he said, “and they’ll tell you everyone’s gonna die. Ask them, In the next 30 seconds? No, no, no, that’s not gonna happen. How about this afternoon? No. What you’re really asking them to admit is, Oh my God, I don’t really exist. I might be gone at any given second.”

Moreover, Ebert has no desire to live forever. “The concept frightens me,” he writes. Instead, he wishes to live such a good life that the kind things he did for other people will ripple outward, long after he is gone. Though never stated outright, this sentiment permeates Defending Your Life. Rather than dangling salvation, purity, and bliss, the film challenges the viewer to accept the unknown that waits on the other side of death as a catalyst to strive for goodness in the here and now. If there is to be redemption, it exists in the present, it is in our control, and the process never ends.

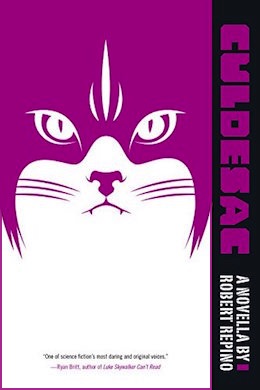

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc (Soho Press, forthcoming). He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop.

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc (Soho Press, forthcoming). He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop.